In fact, it is remarkable how similarly Shelley and Blake view Rousseau’s abandonment of his children in Confessions and how they subsequently deal with father–son relationships in their respective prose and poetry.

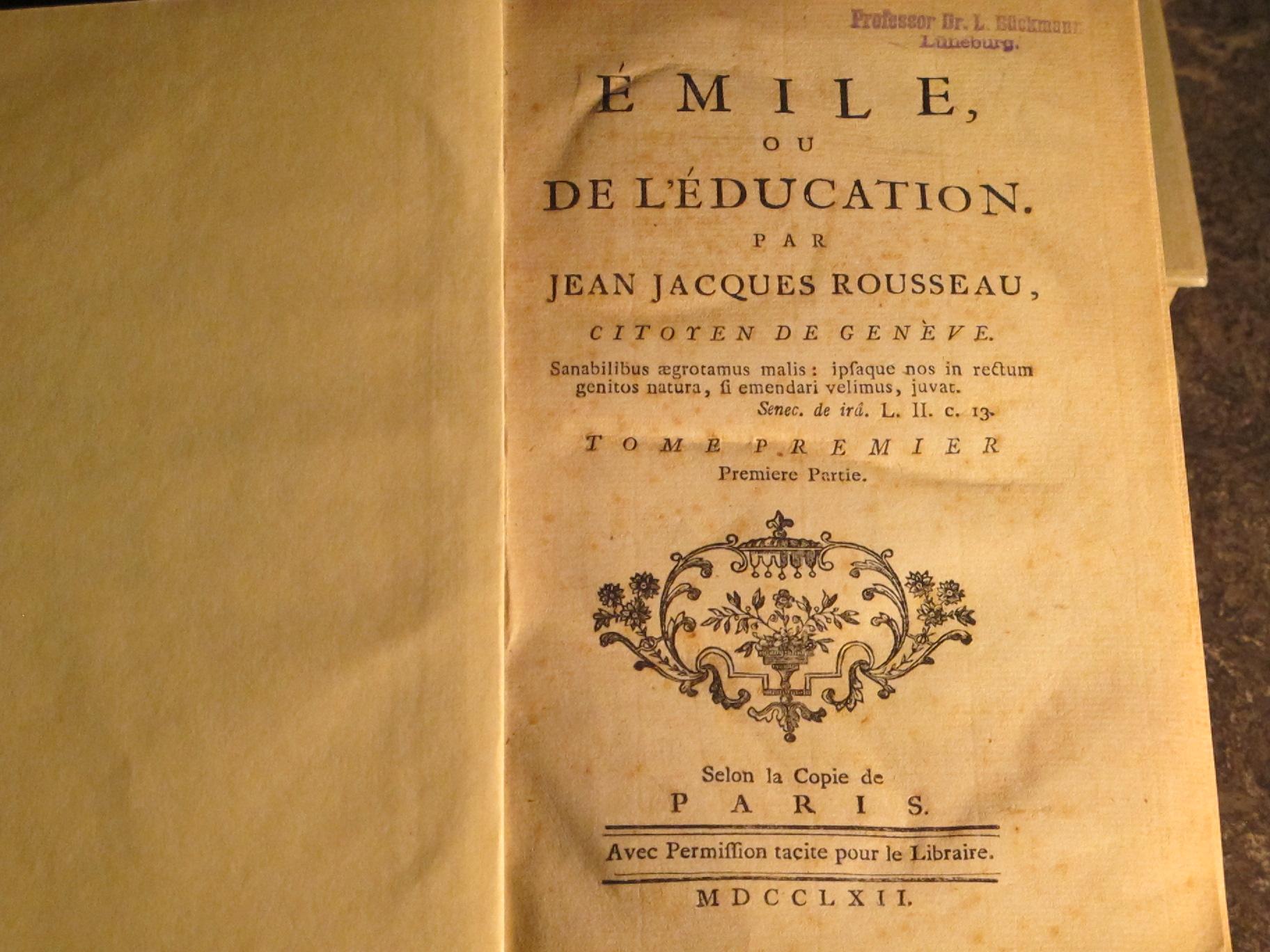

Among the Romantics such vitriol is certainly singular, yet Mary Shelley did not read Rousseau’s work without misgivings. Footnote 5 First mentioned in The Song of Los (1795) and then again in Milton (1804–11) Footnote 6 and Jerusalem (1804–20), Footnote 7 he is subject to persistent ridicule with Blake condemning ‘The Book written by Rousseau calld his Confessions s an apology & cloke for his sin & not a confession’ ( J 738 iii.52.53–5). William Blake was equally familiar with the Genevan philosopher’s works, Footnote 4 though less receptive. Footnote 1 In fact, Shelley had read Rousseau’s Confessions just a year before commencing Frankenstein (1818/1831), Footnote 2 with her journal entries revealing that she continued to reread parts of this ‘invaluable book.’ She was not alone: Rousseau’s influence is tangible in the works of the first-generation Romantic poets William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge as well as the ‘Villa Diodati’ group. Mary Shelley was well acquainted with the pedagogical and political philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau: she had read Julie or the New Eloise ( 1761), Émile or, On Education (1762), Essays on the Origin of Languages (1781), and his Confessions Part 1 (1782) and Part 2 (1789). While Blake and Shelley are rarely brought together in critical discussions, this paper, by looking specifically at the physical and psychological formation of children within the context of father–son relationships, hopes to provide an analytical key which will unlock the way both Romantic writers incorporated personal, pedagogical, and philosophical material from Rousseau in their family-orientated texts.

In particular, both Blake and Shelley pick up on Rousseau’s concerns about the mishandling of children’s bodies as part of contemporary nursing practices in Émile, as well as the way in which the vision of a self-led educational programme is continually undermined by the fear of pedagogical mismanagement. Through their reading of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, William Blake, and Mary Shelley arrive at a similar formula for their respective texts: the mismanagement, neglect, and eventual abandonment of children by their fathers catalyses the development of monstrous progeny in Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818/31), Blake’s Tiriel (1789), The Book of Urizen (1794), and The Four Zoas (1795–1804).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)